Partnerships between big pharma and small biotech companies have highlighted the scramble for assets in a new category of medicines billed as the most important breakthrough against cancer for decades.

Partnerships between big pharma and small biotech companies have highlighted the scramble for assets in a new category of medicines billed as the most important breakthrough against cancer for decades.

Novartis of Switzerland, Merck of the US and its German namesake Merck Serono have all forged alliances in recent days aimed at strengthening their position in the race to develop so-called cancer immunotherapies.

These are drugs that harness the immune system to fight tumours by removing the “invisibility cloak” that cancer cells use to evade detection. In clinical trials, people with advanced forms of the disease have been kept alive for months and in some cases years after exhausting other treatment options.

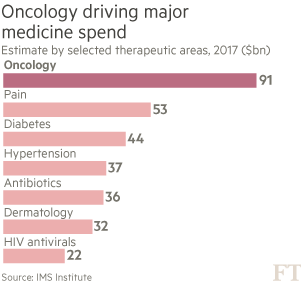

This, in turn, has stirred investor excitement about a drug category that some analysts think could be worth up to $40bn a year within a decade — and intensified competition among pharma companies for the most promising research and development.

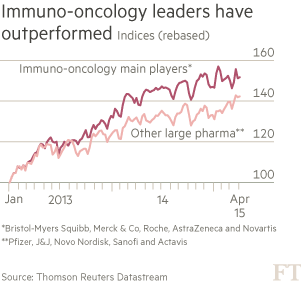

The early leaders are Merck and Bristol-Myers Squibb. They won approval from the US Food and Drug Administration last year for rival melanoma treatments that work by disabling a protein called the programmed death receptor, or PD-1, that normally defends cancer cells from attack by the immune system.

However, everyone agrees that these drugs — Keytruda from Merck and Opdivo from Bristol-Myers — are only a first and imperfect step. While producing impressive results in some patients, more than two-thirds of trial participants showed no response.

This has encouraged other companies to think that, while Merck and Bristol-Myers have a head start, there is still everything to play for. “Checkpoint inhibitors are going to be important, but on their own they will not cure cancer,” says Mark Fishman, president of the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, the drug discovery arm of the Swiss group.

The unsettled science is reflected in the rush of immunotherapy partnerships as companies place bets on different approaches. Novartis, for example, last week teamed up with Aduro of California to develop a technique called Sting, or stimulator of interferon genes, which Dr Fishman believes could provide an especially potent way of activating the immune system.

“If you inject a tumour with this agonist in mice, it not only destroys that tumour but other tumours also disappear,” he says. “So the immune system is being educated to identify cancer. We have effectively vaccinated the mouse against the disease.”

However, the reference to mice brings a reminder that this is early stage science yet to be proven in humans. Novartis agreed last week to pay $200m upfront to license the Sting technology from Aduro with a further $500m dependent on success.

Andrew Baum, analyst at Citigroup, says the deal highlights “the significant value that industry is willing to place on truly novel immunotherapies, even ones in pre-clinical development”. He has likened the potential of immuno-oncology to the antiretroviral drugs that have turned HIV from a death sentence into a chronic disease

Perhaps the greatest buzz surrounds a technique called adoptive cell therapy. This involves removing immune cells from the patient’s body and re-engineering them into chimeric antigen receptor T-cells able to hunt and destroy tumours. Novartis is at the forefront with its CART-19 leukaemia treatment but others are crowding in.

Investment targets immune system

A range of different approaches falls under the umbrella of immuno-oncology. The common factor is that they all involve enhancing the ability of the immune system to identify and destroy cancer cells.

Scientists often describe these techniques as applying an accelerator to the immune system, or removing the brakes that normally hold it back. Of the various types of immunotherapy, two are causing the greatest excitement.

The first aims to disable the “immune checkpoints” that deter disease-fighting T cells from attacking tumours. These checkpoints are designed to prevent the immune system killing healthy cells. But they are exploited by cancer to avoid detection.

The second area attracting heavy investment is adoptive cell therapy. This involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and modifying them in a laboratory with chimeric antigen receptors.

Once reinfused in the blood, these genetically engineered CAR-T cells proliferate into a cancer-hunting army that targets proteins on the surface of tumour cells.

This technique has produced impressive results against leukaemia and other blood cancers in early trials of drugs from Novartis, Juno and Kite. But their potential in solid tumours remains unproven and the great potency of the therapies also brings safety risks.

Read the complete article here Source: FT.com

Ainda não recebemos comentários. Seja o primeiro a deixar sua opinião.

Deixe um comentário